Crossrail impressions, day 1

Whitechapel station is practically unrecognisable from when it was one of my regular haunts. The narrow staircases and passageways are gone. The new, cavernous ticket hall makes the old one feel like a public convenience. The steepness of the escalator shaft down to the new Crossrail platforms is also a little disconcerting—it feels as if I am Mario stepping into a warp pipe, complete with distended cladding on the inner walls that really makes it feel like you're moving through one continuous, sinuous void. What hasn't changed is that there's always more walking involved than you think.

You say 'clean,' I say 'not yet lived-in.' Give it a year and we'll see.

The off-white 'natural' lighting effect is peculiar. In some ways it suggests something futuristic and yet 'homely', maybe like the bridge of the starship Enterprise (TOS, TNG, and Strange New Worlds Enterprise, that is—we don't talk about the Enterprise show.) In others it suggests faded photos of punks and mods lounging about on Central and Bakerloo line carriages in the 70s, bathed in flickery incandescent light.

When the train arrives, it's not quite silent, but it is eerily noiseless. No clattering, no screaming thyristors, no rails sizzling in protest. Instead there is a low build of wind, less a whistle than a deep hum. It sounds less underground railway, more magic carpet. (At least until we get a 'see it, say it, sorted' announcement.)

(I momentarily wonder if taking photos with my camera is going to set off some kind of security alert, but half of London seems to have the same idea. There are TikToks and selfies and Instagram stories and reportage being captured at pretty much every station—to be posted later, natch, because 4G cellular service hasn't been turned on in the Crossrail core yet. Staff are happy to let people snap away to their heart's content with all manner of cameras.)

People are talking to each other about the new railway. A member of platform staff at Paddington chats with the wheelchair user he's met off the train from Whitechapel (presumably listening out for feedback about any snagging issues); a woman sat a few seats across from me on the return journey asks if I've been on this train before (I reply: literally just now, to get here!) This is unusual, but possible, because the train is sealed and air-conditioned. (District, Circle, Hammersmith, and Metropolitan line users had a similar experience when their new trains arrived at the start of the last decade.)

I've probably chosen the wrong seat to sit in, both ways. The Crossrail core's stations all use island platforms, and on each journey I managed to pick a longitudinal seat (along the side of the train) facing the wall rather than the platform. Not conducive to snooping at the architecture and people-watching.

There's a lady sat across from me on the way to Paddington who's outed herself as someone who was up early to get the new train. She's middle-aged, cuts a stylish figure (an all-black pantsuit getup with trainers and some un-flashy jewellery, a dark blonde bob cut that might be a wig) and carries three things only: her phone, which she balances on her knee to use while the train's in motion; an ornate bottle of perfume that's still in its box; and an Elizabeth Line-branded goody bag which she must have picked up at the station in the morning. The must-have accessory du jour?

Between Tottenham Court Road and Paddington, we pass through the unfinished Bond Street station ("STATION CLOSED," "OPENING SOON" read the roundels) and a homeless gentleman comes through the train asking for food and money. No-one has anything to give him. The Elizabeth Line may seem like some sci-fi parallel universe, but it's still London, a city that's desperately wracked by poverty and inequality. (The energy price cap is going up again in October. How many people will soon be warmer on Crossrail than they will be in their own houses?)

Getting out at Paddington, the Crossrail station exit seems to be where mainline station workers congregate for a comfort break. The sun has broken through the rainclouds, leaving a stark contrast between the clouds and the bright, wet brickwork. The roof of the Crossrail station is a peculiar glass affair that looks like a shader has broken in reality—we'll see how it looks when the maintenance budget gets cut and it's allowed to accrue bird droppings and dust. I nip into the Lawn area at Paddington station, accidentally end up in the M&S, and spend a full 95p on a bag of crisps at Sainsbury's. (The cost of living crisis catches up with us all in the end—I remember when these would cost 45p!)

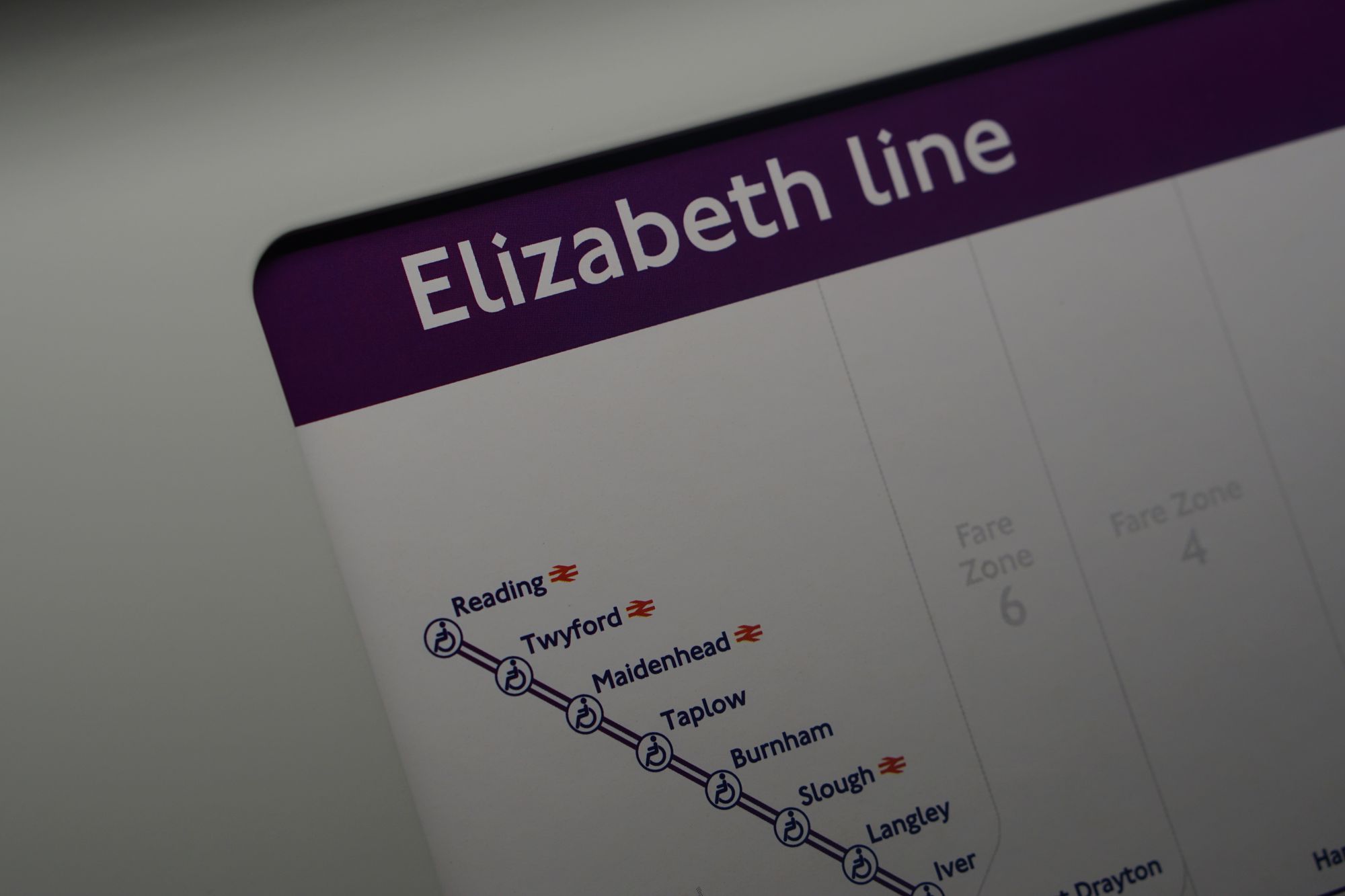

There are some temporary decorations outside the station entrance at Paddington, apparently from Marylebone Boys' school (if the destination board on the painted train is any indication.) The bunting might be for the opening of the line, or it might be for the Queen's imminent Platinum Jubilee—or both. Boris Johnson did rename Crossrail after her, of course. At least the bunting is a cute temporary curiosity, even if it's a facsimile on closer inspection. Another photographer seemed interested.

For the person doing the platform announcements at Paddington, the novelty has clearly worn off by around 7:30pm—they sound exhausted by the mere concept of platform screen doors, having presumably spent the whole day telling people not to lean on them. Maybe that explains why one of the sets of doors is out of use.

There's a typeface interloper on the departures boards. They're high-density screens positioned above the doors, which is really where they always should have been—but better late than never. Almost all the text is in crisp, bold Johnston, save the interchange markers, which suspiciously look like they might be in Segoe UI. I don't want to know what this tells us about what kind of infrastructure (or which version of Windows) backs Britain's newest railway.

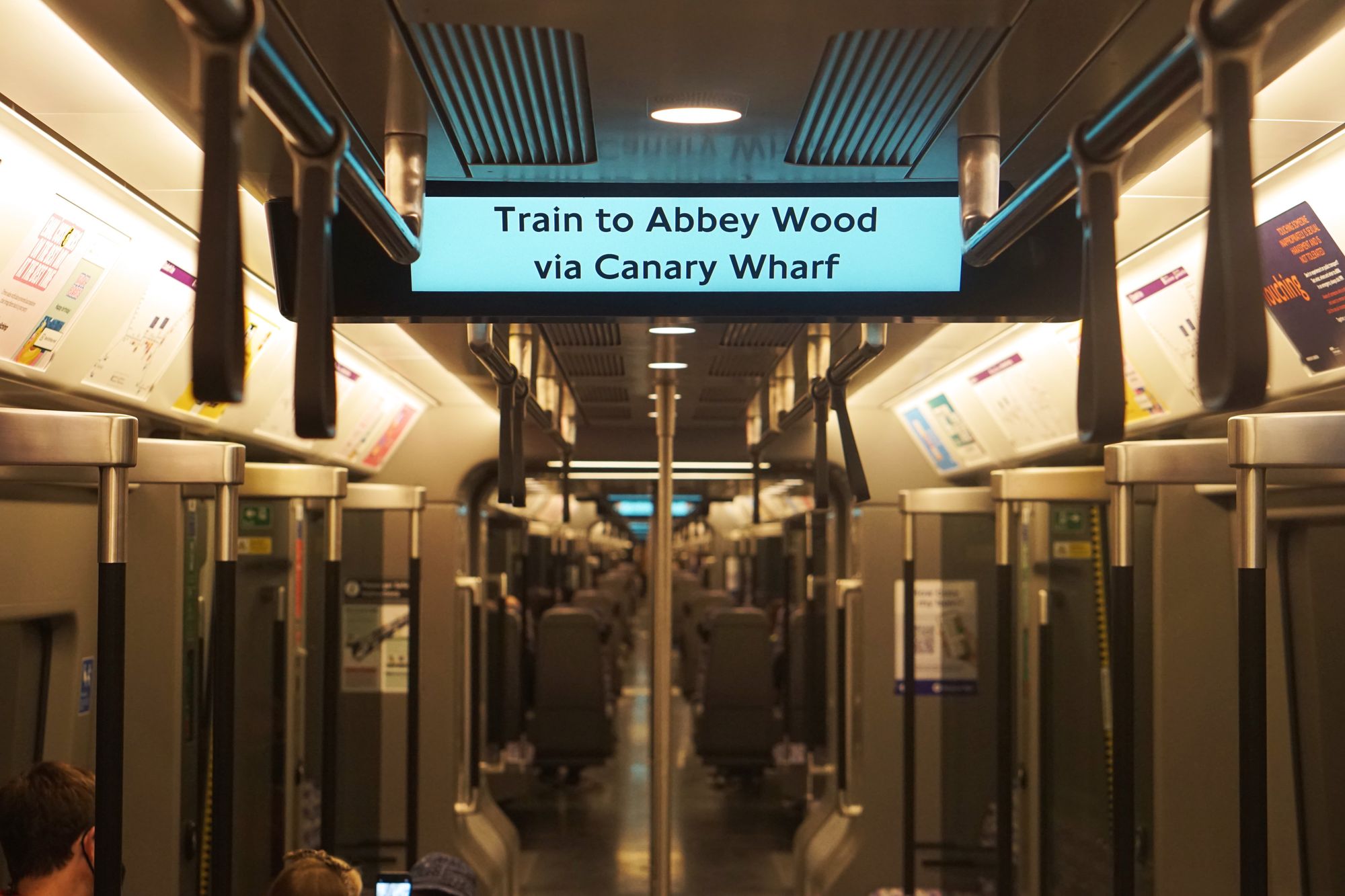

The eastbound train I take is a little noisier, but still allows for eavesdropping. A woman getting on with her friend for one stop—her friend thinks for a moment he can go directly to Stratford on this train (he can't.) A man explaining to his two kids that "Abbey Wood via Canary Wharf" means "imagine there's more than one way to get to Abbey Wood [there isn't—ed.] so saying 'via' means it goes through Canary Wharf—actually I think it's the Latin word for road—" etc. etc. until they lose interst and ask him how many stations there are on the Waterloo and City line. A group of students hopping between stations and taking photos, with one decamping the group at Whitechapel because he wants to see a sign on the door. A man recounting to his colleague (as they both try the line after work) that he went to Abbey Wood during lockdown, and was amazed to discover it had both an abbey, and a wood.

Canary Wharf, where I change onto the DLR to get home, looks rather underwhelming all things considered. Metal pillars, tiled surfaces, light boxes that will no doubt be taken up by obnoxious advertising in good time: it all feels a bit generic. (Canary Wharf Jubilee line station was famously used as the interior of the Death Star in Rogue One: for the Crossrail station it seems to have been designed with generic sci-fi series' filming budgets in mind.) Not even the yellow escalators is enough to make it exciting.

"Better late than never" is the phrase that comes to mind as I get lost in Canary Wharf shopping centre on my way to the DLR. Here is a project which has been under serious consideration for pretty much all my life, and under construction for over a third of it. Britain is terrible at large infrastructure projects so frankly it's a miracle Crossrail got this far. One can only hope that its immediate success (and maybe some timely political changes in Westminster) might expedite investment in more infrastructure, everywhere—because we truly can't afford to wait another thirty years to fix the next problem.