THE MILQUETOAST WAR: What went wrong with the Halo TV series

Like loading the Master Chief's helmet into Microsoft Excel and using the fill tool to decide what's inside

There has never been a great adaptation of a video game into a film or TV show. The closest I’ve seen is the Detective Pikachu movie, which is entertaining but no better.

Some day, someone will make a successful TV or film adaptation of a beloved video game that avoids the typical pitfalls, and presents a creative vision so profound that it transcends the medium and puts snobbish naysayers in their place. Maybe it shall be Super Mario Bros (2023), but after hearing Chris Pratt's Mario voice I'd say the odds on that are short.

HALO is decidedly not a great adaptation. It is a show that squanders its talent on a story that, for all its use of gore and violence, is offensively anodyne. Now and then, the show acts like it’s about to say something interesting about class or imperialism or militarism—but it dances around making a point and never lands a clear blow. It offers an offputting facsimile of the video games’ aesthetic, but misunderstands almost everything that makes them compelling. It does not realise that the world has moved on since 2002. The first season of HALO The Series is a hot mess and a spectacular miss.

So what went wrong?

PART I. Introducing an audience surrogate character & promptly forgetting she exists

"Kwan's storyline is so far separated from the Master Chief's that she is, to all intents and purposes, a sideshow"

The idea of turning the HALO games into a TV show has existed for over a decade, after attempts at a movie with Peter Jackson’s name attached to it fizzled out into nothing but an unmade draft screenplay written by Alex Garland and a glorified HALO 3 trailer by future District 9 and CHAPPiE director Niell Blomkamp.

In that time, HALO spin-off series have appeared: TV shows of quality ranging from “meh” (FORWARD UNTO DAWN) to “eh” (NIGHTFALL) to “execrable” (the animated FALL OF REACH) plus one audio drama podcast. But these have all been tie-ins to the mainline game series. We’ve not seen anything that attempts to tell the story of the games in a purely visual medium. There’s one reason for this: the Master Chief.

In the games, Master Chief Petty Officer Spartan-117 is an implacable figure who says very little (franchise director Frank O’Connor describes a choice early in the development process to make him ‘laconic’.) He isn’t a Duke Nukem character who punctuates every other sentence with a misogynist joke, nor a silent Gordon Freeman type. The Master Chief’s voice, provided by Chicago radio DJ Steve Downes and sounding like the patina on an indestructible pair of walking boots, is principally used to advance the plot and explain things to the player. When Chief makes a wry joke, it’s a rarity—when he expresses an emotion (as we saw to great effect in HALO 4 and HALO INFINITE) it’s a shocker. We also never see the Master Chief’s face. His head is framed out whenever his helmet is off. In HALO: COMBAT EVOLVED, Bungie wanted anyone to be able to play and feel it was their own face behind that visor.

You can argue as to whether this was successful or not, particularly in the generally underwritten original trilogy of games. But it led to conventional wisdom, for many years, that any HALO movie or TV show could not follow the Master Chief himself as a conventional protagonist. Instead, it would need to focus on the people around the Master Chief, and how they react to him—at least initially, until we are at a stage where we can comfortably explore the Master Chief himself.

This seems to have been what the show’s creators had in mind, at least from episode 1, where we meet Kwan Ha (played by Yerin Ha, who is wasted on this script.) She’s a child of revolutionaries on planet Madrigal, and we meet her on a mine, surrounded by salt-of-the-earth types who are suspicious of the government. The show dresses Kwan and her friends in what look like sewn-together car seat covers and potato sacks, just in case you didn’t realise these people are peasants. (In fact they're reasonably well-to-do because it turns out deuterium mining is a lucrative business—this will be important later in the show—but for now, HALO stresses that Kwan, and the people around her, are outside the bosom of the UNSC, and therefore both 'working class' and 'other.')

The series opens with the mining outpost, including Kwan’s father, being gruesomely massacred by aliens with plasma weaponry. Fortunately for Kwan, a fireteam of Spartan supersoldiers, led by the Master Chief (Pablo Schreiber) arrives just in time, falling from a dropship like a set of action figures being dumped outside a charity shop. They defeat the aliens, but too late. Kwan is the only survivor.

Alas for Kwan, Chief isn’t here for her. The Spartans are on Madrigal to recover the “Keystone,” an alien MacGuffin du jour that gives the Master Chief—and only the Master Chief, for some reason—a sequence of visions on contact. Kwan is left wandering alone, only to be picked up later when it’s convenient to the plot (which cleverly foreshadows how the show will treat her storyline.)

What’s particularly infuriating about this is the hope that HALO gives, just for a moment, when Chief and Kwan actually sit down and have their first proper conversation. There is a shadow of an interesting and even groundbreaking prospect in here, and for this, you need to understand that the Spartan programme, in the games as well as the TV show, was originally developed as a tool for an authoritarian human government to crush rebellions. The threat from the alien Covenant came later. The reason the UNSC kidnapped children and replaced them with dying clones, forced them into servitude as soldiers, and mutilated them, was not to defend humanity against an imminent existential threat, but to tighten its own grip on its outer colonies.

The show surfaces this tension in a deliciously awkward two-hander: Kwan reminds the Master Chief that he killed her mother. It was some years ago, at an insurrectionist meeting, where a Spartan fireteam was ordered to eliminate an ‘imminent threat’ while responding to a presumably spurious bomb alert. The Master Chief tries to justify his actions, but can’t. There is a kind of electricity in this scene, a potential to do something exciting. As Sam Machkovech’s review of episodes 1 and 2 for Ars Technica says, “HALO had to reach its fifth full-length video game before toying with the idea of Master Chief being a bad guy… [the] TV show gets there within its first 55 minutes.”

So, at the end of episode 1, it feels like HALO might be willing to subvert its source material, and reckon with the Spartans as a component of an imperialist machine in ways the games have barely flirted with.

Alas, two episodes later, this plot thread has been all but forgotten. Kwan has been sent off to the Rubble, a seedy space medina with narrow passageways and marketplaces crowded with extras (wearing rags, of course, because they’re poor and coded brown) under the protection of Soren (an AWOL Spartan who’s now a privateer with a trench coat, because of course he bloody is.) From there, she doesn’t get to do much except seethe about the importance of her father’s revolution, plead with Soren to take her back to Madrigal, and glare at news reports of her home’s takeover by UNSC collaborator Vinsher (Torchwood’s Burn Gorman, in probably the worst mis-casting of a quality character actor since Marwan Kenzari’s Jafar in the 2019 Aladdin remake.)

Around two thirds into the series, having given her the measliest shreds of a B-plot possible to that point, HALO suddenly remembers that Kwan exists, and gives her an episode of her own. It’s heartbreaking because Inheritance, a largely isolated yet visually striking episode directed by Jessica Lowery and written by Steven Kane, for all its reliance on orientalism and fantasy cliché, might've been good if it wasn't part of the show's mediocre whole. (A surreal sequence in a tent is a much more effective version of the Master Chief revealing his face than we got in episode 1, foregoing an extended Transformers-style helmet disassembly in favour of stark shot/reverse-shot hard cuts and lighting by fire.) Kwan finds herself in the middle of a desert talking to an echo of her dead father, in a scene that is nicely shot (even if the plot, something about a Forerunner AI and a magic portal, makes zero sense.) She allies with Soren and agrees to work with him to defeat Vinsher in a thrilling two-versus-many action sequence that plays out like a tense HALO multiplayer match. Soren and Kwan part on amicable terms, and… that’s it. Kwan Ha’s story is over.

We don’t get to see Kwan rallying her people around her and declaring Madrigal’s independence. She gets no closure beyond smiling in the rain after blowing up Burn Gorman. She isn’t even mentioned in the series’ final two episodes. Our audience surrogate character has been discarded because she is no longer useful. For now, at least, the story of Kwan Ha is not her own. She was only there to trigger an epiphany within the Master Chief (and to get him to take his helmet off.) To quote Renata Price’s review for VICE, “Kwan Ha’s half of the narrative is a collection of shorthand plot devices with no emotional or intellectual foundation.”

For better or worse, HALO has always been a story about the West. The United Nations Space Command is, to all intents and purposes, the US military, or perhaps NATO, in space. They are engaged in a forever war against the Covenant, a multi-species coalition of religious extremists who seem intent on wiping out humanity. (In early versions of the HALO 2 script, the Arbiter, an assassin who ends up defecting to work with the Chief, is called “The Dervish,” sure to make those aware of Sufism cringe with a massive 'yikes.') All the while, the UNSC brutally oppresses uprisings across human controlled space, going so far as to mutilate children and force them into labour as soldiers under the auspices of the Spartan programme to give the regime an advantage.

The games can never really touch on the UNSC being an empire-in-all-but-name. It’s no fun being the boot if you think too much about whose foot you’re on, and what you’re being used to stomp. The tie-in books are at least willing to entertain the possibility that the UNSC might not be a benign entity, even if their politics are dictated by the author and still view Project SPARTAN as a morbid inevitability.

The TV series, and particularly the character of Kwan Ha, was therefore an opportunity. The creators have spoken about the desire to show a world beyond the military bubble of the games, and even made changes to the games' timeline (the right choice, in my opinion) to make the Insurrection and the Covenant War concurrent. Everything has been teed up for HALO The Series to reckon with the UNSC's imperialist leanings and interrogate what makes the Master Chief's myth so alluring, winding it into a story about how class and empire work in the context of a military-industrial complex that is fed by conflict and human suffering.

But Kwan's storyline is so far separated from the Master Chief's that she is, to all intents and purposes, a sideshow, unimportant to the main happenings of the plot. HALO The Series opened with her, toyed with using her as an audience surrogate character, then decided it was no longer really interested in telling her story. What a waste.

PART II. It kinda looks like HALO... to begin with

"...an aesthetic that is homogenous, dated, and maddeningly incomplete"

The first HALO game opens on the bridge of an ageing warship that’s outnumbered, outgunned, and is being outrun. When we meet the Master Chief in the second game, he’s being scolded by a technician for his equipment having been destroyed in the previous game. “You know how expensive this gear is, son?” he scoffs, as he tosses out damaged armour components, no doubt thinking about the spreadsheet he’s going to have to fill out and which cost centre he needs to charge it to.

HALO presents not so much a ‘used future’ aesthetic as a ‘junk future.’ Everything the UNSC uses feels like it was put out to tender, value-engineered into a grimy lump, and built by the cheapest bidder. In the AM/FM continuum of Actual Machines vs. Fucking Magic, we’re definitely dealing with creaky, rattly, plasticky machines. They probably run Windows XP too. No wonder humanity is losing.

Everything in the HALO TV show feels like it was designed to look like a high fidelity replica of something from the games, and this is a problem.

The TV show does an acceptable job of cribbing from the low-res mid-2000s aesthetic where a reference is present in the source material. The ships look right. The uniforms look OK, mostly. The aliens look similar to their appearance in the games, albeit never quite fluid and tactile enough to create the illusion of a living thing rather than a 3D model. The Mjolnir armour worn by the Spartans looks like cosplay inspired by the cover art on the books.

Things fall down completely when we see something—an environment, a prop, a model—that doesn’t appear in the original game. In what I presume is an attempt to emulate the flat textures of the Mombasa highway chase in HALO 2, the military base on planet Reach feels like an underground car park. Not just the loading bay, or the hangar… no, all of the base follows this design language. The situation room, the offices, main atriums and corridors, a block of ablutions which inspires a deep sense of existential dread—all have the same grimy concrete walls and dim lighting that suggest a motorway underpass that smells of piss.

The constraints of making a TV show are evident in HALO’s location choices. In episode 4 for instance, the Master Chief returns to his home planet, whose flora and fauna look suspiciously like woodlands outside Budapest—because they are. In one of the better sequences in episode 3, the Master Chief takes a train for presumably the first time in his life: “Reach City Transit” is clearly line 4 of the Budapest metro with some decals and futuristic-looking ticket machines added (because HALO is apparently set in a world where contactless payment never happened, so people still queue up to buy train tickets half a millennium from now.) This bleeds through to the sound design, where cars and trucks make internal combustion engine sounds—which, yes, they do in the games, but 20 years have passed since then, and these days taxis and hire cars and buses hum and purr rather than growl and roar. It's a small detail, but feels like a crack in the futuristic production design.

Using real locations isn’t necessarily a problem. The Death Star in Rogue One was a re-dressed Canary Wharf London Underground station, and the movie used its futuristic architecture to great effect. Alien planets in Doctor Who famously look like quarries with matte-painted backgrounds. And the games do this too—in HALO: COMBAT EVOLVED, the vegetation and landscape on the Halo ring suggests the Pacific North West.

But suspension of disbelief is a fine art. HALO The Series presents an aesthetic that is homogenous, dated, and maddeningly incomplete. When we meet the mastermind of the Spartan programme, Dr Halsey (Natasha McElhone) she’s in her private laboratory, which looks like one of those little darkened rooms in art galleries where they play short films. The naval operations centre on Reach looks less like a situation room for complex and fast-moving military command decisions, and more like an Apple Store circa 2004 staffed by fascist cosplayers.

Had HALO appeared in 2008, this might’ve been novel. But since then, we’ve had shows like Westworld, The Expanse, and the Star Wars and Star Trek spin-off media, all of which are on another level of visual coherence. Some of the later HALO games have been criticised for dropping the rugged militaristic feel in favour of generic sci-fi textures, and this is a trend the show continues when it has no visual reference to mimic. Throughout much of HALO The Series, one wonders if any particular frame could’ve come from any sci-fi show. Its view of the future seems to have come straight from 2002.

And speaking of things that may have come from any show, we need to address the gore.

At the beginning of HALO episode 1, a teenager’s head explodes after being hit by plasma fire. We then see three other children being spattered to death, including one whose legs are vaporised by one bolt before the rest of them is taken out by a second. Kwan spends the whole episode with a blood spatter from her dead friend on her face in a cheap bit of 'final girl' shorthand. The Needler, a weapon that fires explosive penetrating projectiles, is used to startling effect on an unlucky soldier in episode 4. This is brutal and somewhat effective, but considerably more graphic than the Indiana Jones-level violence of the games.

It’s not just in battle sequences that we see often gratuitous levels of gore and violence. In episode 2, the aforementioned Vinsher shoots prisoners with bagged heads, point-blank, one-by-one. Episode 3 begins with a child labourer being murdered and another being scarred for life with a shock baton/taser thing. Kai and Riz, two of the Spartans on Master Chief’s fireteam, are subjected to horrendous injuries throughout the first season. In the closing minutes of the last episode, the Chief cauterises a fully-conscious Riz’s exposed lungs and intercostal muscles with a gas flame, which doesn’t seem like it has any medical rationale. (The show more readily inflicts appalling, visceral pain on women characters than it does on men.)

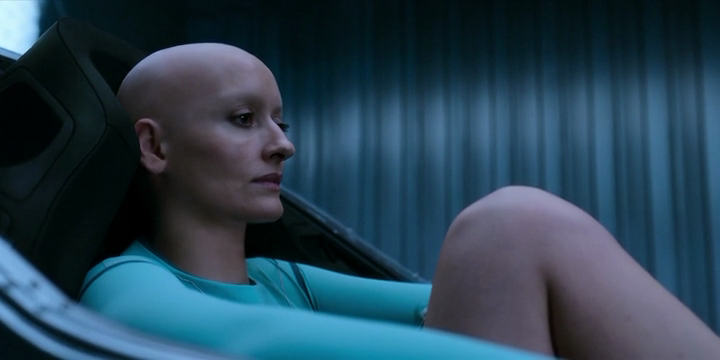

I think this aspect of HALO’s approach can be summed up with how it deals with Cortana. I actually like her appearance in this show, and I’ve seen it praised for updating her look from the games while jettisoning some of the elements that make less sense (the nude body-suit thing, for instance—explained away in canon as her ‘trying to unsettle people with her looks,’ but really because it was the early noughties and everyone assumed all gamers were horny cishet dudes.) As in the games, Cortana is played by Jen Taylor, a stage actor who’s had over two decades to fashion this character around her.

Things go off the rails, though, when the show decides to show the creation of Cortana, something we don’t see in the game canon. In HALO, artificial intelligences are created by scanning and modelling a human brain, which destroys the original. Most donor brains come from people who’ve recently died, but Dr Halsey cloned her own brain using a rapid, morally-questionable, and extremely illegal method to provide the basis for Cortana. (One of the spin-off books has the Chief recovering spare brains from Halsey’s ruined laboratory for complex sci-fi reasons.)

HALO The Series does not consider this an interesting enough moral quandary in and of itself, so throws some eye trauma and sexual assault into the mix.

Instead of cloning just her brain (which would presumably be cheaper and allow you to scale more easily, and hardly be beyond the technology of the 26th century) Halsey is growing a full-size clone of herself. All of it is distressingly extra. The clone wearing make-up, having a bald scalp (but intact eyelashes for some reason), the egg-shaped pod from which she emerges. Maybe she should’ve added some prosthetic horns on her forehead to complete the look.

Of course, because this is a TV show for Serious Adults, the only way to extract the clone’s brain material is to jab a needle into her eye while she’s still awake and conscious (albeit chemically paralysed.)

In case that isn’t enough, just before she’s about to have her neural substrate sucked out through her pupil, Halsey’s assistant, Adun, sexually assaults the clone.

I’m giving that a line of its own because it’s something that comes out of absolutely nowhere. He whispers to Clone!Halsey that she has a ‘beautiful brain,’ and moves in as if to kiss her. Adun is an original character to the show, so this was a choice on the half of the producers and writers—but it’s not clear what purpose he serves here, other than to make viewers uncomfortable. (He does get his comeuppance in the season finale, but is soon after replaced by his own clone.)

The whole eye-poke sequence goes on for much too long. We have over a minute of the needle rotating on a robotic arm and hovering over the clone’s eyeball, her breaths becoming more and more panicked. It’s disturbing, but not because we are invited to empathise with the clone. The shot choices and editing revel in the clone’s terror and excruciating pain in her final moments. Watching her being harvested feels voyeuristic.

And the biggest question I was asking myself while watching this was, “who is this here for?” One wonders if HALO’s producers saw the trend for more gore on TV—skulls getting crushed and people being waterboarded with wine in Game of Thrones, the unnecessary eye-pulling thing in Picard season 1, disembowellings in Jessica Jones and faces being sliced open in The Boys—and decided they needed to amp up the levels of violence to indicate to viewers that this was a Serious Adult Drama in which Serious Adult Things happen.

And yet HALO assumes that Serious Adult viewers will not understand that Dr Halsey is a morally reprehensible eugenicist with a god complex who it’s OK to dislike, unless she is shown directly visiting physical violence on another woman.

(Would Serious Adult viewers with a functioning moral compass not have already got that idea from, you know, Halsey kidnapping children and training them as soldiers?)

PART III. McMansion world building

The series casts HALO as the tale of a chosen prince who must save the world and get the girl

Halsey’s clone being fully conscious and aware of her own brutalisation to create Cortana was not the only place where the showrunners decided to put their own spin on HALO’s internal logic.

Around twenty minutes after the aforementioned eye-poke thing, we see the Master Chief’s arse. For all the uproar the Master Cheeks generated, you don’t need a ‘valid reason’ to be naked. (Vinsher clearly doesn’t, as a weird clandestine meeting in a bathhouse with cigars shows.) In this case, he's in those weird liminal ablutions in the Reach base, preparing to perform makeshift surgery on himself. In the internal logic of the show, this makes sense.

The bad news is, the makeshift surgery (which Cortana helps with in a cute couples’ trust-building exercise) is to remove the Master Chief’s emotion chip, which is something Spartans have now.

OK, they’re “hormone pellets” that suppress emotions (and for some reason also stop them being able to taste foods.) The Master Chief, frustrated at being unable to interpret the visions of his own childhood he sees when touching the magic alien stone, removes his and realises that now, suddenly, he can empathise with others’ emotions. He looks at the sky, he partakes in some people-watching on a train, he is momentarily transfixed by some live music and a dog that looks like his childhood pet.

For all the song and dance the show makes of this, removing the emotional regulator ultimately makes no difference to the Master Chief’s actual mien or personality. When his squadmate Kai does the same thing shortly after, it marks a turning point in her character arc, making her significantly more interesting (put a pin in that—we’ll come back to Kai.) But for the Master Chief, who is nominally our main character, cutting the pellet out of his back is just a gate to be cleared in HALO season one’s overall story arc.

Because the Master Chief’s emotion pellet is also the thing that stops him finding out the truth about his abduction into the Spartan programme.

Let’s rewind a bit here. In HALO The Series, the Spartans have had memories of their childhood chemically suppressed, including those of their abduction at age six into the Spartan programme. This is another addition to the show’s lore which was not present in the timeline of the games, and in fairness the emotion chip and wiped memories are not implausible: admirals might be more comfortable granting funding if they had an insurance policy against their investments being compromised by rage or grief or fear on the battlefield, or realising the horrors of their own past and staging a coup d’état.

To be charitable to the show, some of the changes in service of this plot thread work reasonably well. Dr Halsey, for instance, is considerably more controlling and conniving than she is in the games’ spin-off media, and is genuinely obsessed with her vision of the Spartans as humanity’s next step. (Natasha McElhone strikes the perfect balance between a façade of earnestness and an intense calculating interiority, and is easily one of the show’s brighter spots of casting.)

But some choices are just strange and defy logic in a way that’s at odds with the series’ wannabe grimdark aesthetic. Why, for instance, would an alien artefact that’s supposed to indicate the location of the titular Halo ring (the series’ true MacGuffin) show people visions of their own childhood? Why would the Spartan programme’s origin in kidnapping children seemingly be an open secret on the UNSC base at Reach City, but be unknown to the Spartans themselves? Why would Captain Keyes, father of Halsey’s estranged daughter Miranda, continue to be so deeply involved with the Spartan programme after his and Halsey’s apparent divorce—would no audit realise that the personal situation is highly irregular and begets a potential security risk? And why is Miranda, a linguist and scientist, the person they choose to de-brief Kwan, a committed rebel, in the hope of making her into a propaganda tool? Does the UNSC have no professional negotiators?

The show gives itself a great deal of legwork to explain why the Spartans don’t remember their childhood, but does not do this in order to set up a puzzle-box style mystery. HALO makes it clear to the viewer very early on that the Spartans were trained as child soldiers and removed from their parents at a young age. Halsey all but says it in episode 1. Episode 2 features a teenage Master Chief allowing Soren to abscond from the programme. In one of the brighter spots of episode 3, the Clone!Halsey asks the Ur-Halsey about how many children survived the augmentations procedure (35—fewer than half, it turns out.) Episode 4 opens with young children undergoing brutal military training, with captions superimposed showing us that this is the Master Chief and his team. The show clobbers us over the head with the Spartans being child soldiers, but the only tension in this plot line is that the Master Chief doesn’t know he was abducted from his parents, and will get angry when he finds out. Baby’s first dramatic irony. Soap operas do this kind of story all the time, and do it better.

This kind of upside-down storytelling is typical in HALO The Series. During episode 1, where viewers unfamiliar with the games are presumably supposed to be wondering if the Master Chief is a robot or not, he runs a diagnostic on his suit, which oddly requires him to read out his full name to a computer: “Master Chief Petty Officer John-117.” Watching the show bring a close to the episode by having the Chief remove his helmet (and shooting it with a deep reverence, practically a nudge and wink to fans of the game) may well make casual viewers scratch their head—the show already heavily implied he’s human by giving him a human name! Why, they might wonder, does HALO treat seeing the fleshy face behind the visor as such a pivotal moment?

The answer is, “because the show is incapable of subtlety, particularly where it’s actually necessary.” And this presents a further problem, because while HALO is going over itself again and again to reinforce the vague moral it thinks it wants you to take away, it doesn’t fix any of the more creaky aspects of the source material, and in many cases makes them worse.

HALO has always suffered from great-person syndrome, particularly in the early (and more pulpy) spin-off media. Dr Halsey, the universe’s resident omnidisciplinary scientist, is a jack of all trades who isn’t afraid to get her hands dirty. She creates and presents the modelling that justifies Project SPARTAN’s existence; she designs the Spartans’ cybernetic augmentations and the Mjolnir armour; she clones her own brain to create Cortana. She even visits the children at their schools, deciding to add a six-year-old John to the abduction list when he successfully guesses which way up a coin will land.

It does stretch believability that all of this would spring from the brain of one person. All these details come from video game tie-in media, after all. But crucially, the core concept—that an imperialist military apparatus could kidnap people, mutilate them, and turn them into soldiers—is utterly believable. Like thrillers such as The Bourne Identity before it, HALO posits something reminiscent of MKUltra but involving children. It doesn’t matter that it’s the creation of a suspiciously small cast of characters. The point is that it’s something that gets approved, funded, and supported to completion, despite being morally repugnant.

HALO The Series does toy with The West Wing-style politicking, with snatches of intrigue showing Halsey manipulating her way into getting funding and approvals for her experiments. And we get brief appearances from stupendously famous actors as the admirals (Bollywood legend Shabana Azmi as Parangosky, and Kier Dullea of 2001 fame as Hood.)

But the cast of leadership in the orbit of the Spartan programme is even smaller than it is in the tie-in novels. Captain Jacob Keyes (Danny Sapani) who in the game canon is implied to have had a brief fling with Halsey and not been fully aware of the Spartan programme until after his involvement ended, is promoted to ‘captain’ of the programme and is explicitly one of Halsey’s collaborators in the series. His and Halsey’s daughter, Commander Miranda Keyes (Olive Gray) is no longer commander of her own starship, but a scientist whose main interest seems to be linguistics—although of course, she has her mother’s jack-of-all-trades mentality when it comes to investigating the magic alien object, because all areas of science are interchangeable. And Halsey herself seems to have her hands even deeper in the Project SPARTAN pie than she does in the books: she’s shown being present at the actual kidnapping of the Spartans. Doesn’t she have other stuff to do? I have no doubt she designed the logo, printed the t-shirts, and played saxophone on the Spartans’ theme tune too.

These five people—Halsey, Parangosky, Hood, Keyes Sr, and Keyes Jr—are the only command staff I can name off the top of my head from the series. Any time we see the bustling operations centre on Reach, it contains a maximum of three important characters, surrounded by extras. The same goes for the Spartans, of whom we only ever see five: Soren (a very different version of whom appears in the game spin-off story Pariah written by B. K. Evenson), Riz, Vannak, and Kai, who appear to be renamed versions of the game!Chief’s squadmates Linda, Frederic and Kelly, and the Master Chief himself. One gets the impression that everyone knows everyone. Far from feeling like a functioning military installation and nerve centre of an empire in all but name, it’s impossible to believe there’s anything more under the surface than the average escape room set.

This ‘small world’ property of the UNSC does a disservice to the characters, and to the actors. While Parangosky’s working relationship with Halsey is frosty, it reaches nowhere near the delicious levels of tension caused by their fundamental philosophical disagreements in the books. In the opening episode, Keyes Sr tells his daughter that Kwan Ha has been listed for assassination because of her refusal to co-operate, something massively out-of-character for a captain shown in the games and books to be morally principled and uncomfortable with his role in the recruitment of the Spartans. Despite Olive Gray's performance (which was lovely, and resonated with me as someone who permanently suffers from impostor syndrome) Keyes Jr mainly functions as a sounding board for other characters; her only real discovery comes just a moment too late to avert a catastrophe. She gets no real agency because every action she takes is in the shadow of her mother—useful for showing us how controlling Halsey is, but to the detriment of allowing Miranda to exist as a character in her own right.

To give the show credit, when it allows Danny Sapani to actually play Captain Keyes, he’s terrific. There’s an uneasy but genuine avuncular connection with the Chief, and Keyes’s guilt about his involvement in the programme’s origin is a great source of inner turmoil. One scene in episode 9, in which the two obliquely address the topic of their pasts, was just right, playing the tension of their mutual, almost-familial affection, countered by the Chief's sense of betrayal and Keyes's shame, like a fiddle. I’ve contemplated writing this fanfic. The actors truly sell it.

But HALO’s script takes almost half its runtime to get to this stage. It should not take us this long to want to root for these characters. Battlestar Galactica managed it two decades ago, and the current TV genre fiction landscape offers shows like Strange New Worlds, The Rings of Power, Severance, The Umbrella Academy et al, whose characters draw you in from the get-go. Instead, HALO coasts on the goodwill of those who recognise the Master Chief from the games, and does very little to invest us in anyone who is not him. And lest we forget, this show has been in development for over a decade.

By comparison, HALO: THE FALL OF REACH, a prequel to the games and the Master Chief’s origin story, was written in about seven weeks in 2001. Its plotting is stringy, its dialogue is plain, and the prose workmanlike, but there’s some lovely character work in there. You can read it, and come away feeling like you understand the Master Chief and the world he comes from. Writer Eric Nylund had only a story bible and multiple iterations of the (unfinished) script for the game to work from. On the other hand, HALO The Series has had 10+ years of development work, industry heavyweights such as Steven Spielberg, and almost 20 years of games and spin-off media as source material to calibrate its tone and internal logic. It then proceeds to completely fumble it. When the characters in a TV show feel more flat, and the logic feels more flimsy, than in hastily-written tie-in media that exists primarily as a marketing tool, something has gone desperately wrong.

This is why HALO The Series reminds me of one of those hideous McMansions. It is the adaptational equivalent of taking a timber frame and loading it with a tasteless mock-gothic façade made entirely out of foam—probably inspired by a mood board of ‘things you saw on TV and liked the look of.’ In trying to demonstrate its Serious Adult nature, HALO loses both the sense of wonder and weirdness and the grounded militaristic element from the games, producing something both logically inconsistent and unremittingly bland. Remember the horny furry conniption that was CATS (2019 dir. Tom Hooper)? It’s easy to mock the terrible celebrity improv and the ruined musical numbers and the digital fur that was the colour of human skin, but the rot extends deep into structural issues that simply weren't present in the stage musical. As summarised by Lindsay Ellis in her review:

The plot [of CATS] was always paper thin and flimsy, and it was that by design. But the film doesn’t make the plot, such as it were, less flimsy. It just creates more of it, and more nonsense that the film obligates itself to explain, because we have committed ourselves to the style of realism and logic.

Remind you of anything?

And this is just the characters and plot points the show imports wholesale from the urtext. The show invents additional characters seemingly for the purpose of showing a world beyond the militaristic bubble of the books and games, but then forgets to do anything meaningful with them. As mentioned above, Kwan Ha is practically discarded after episode 2, her storyline stuck together with blu-tack and entirely separated from the Master Chief’s—a waste of a superb actor in Yerin Ha. Adun, as mentioned, only seems to exist as an aloof and sinister sidekick to Halsey.

And then there's the character the show seems most enamoured with.

Makee, played by Charlie Murphy, is another character devised for HALO The Series, and she is a human member of the Covenant. This attracted a great deal of controversy when the plot line came to light in the run-up to the show’s release, but I was willing to entertain it: the Covenant have always been a multi-species religious coalition, and of course there would be a contingent of humans lining up to join a death cult and accept the holy word of their new alien overlords. And adding a human element to the Covenant makes economic sense for the production—if a two-hander on the Covenant side can involve one human actor and one computer-generated character, that’s going to require less VFX work and less rendering time than two alien characters talking to each other. By throwing a human element into the Covenant, there was an opportunity to tell a compelling new story that was still recognisably HALO.

(If you’ve been reading this review so far, you know that the show is not good at taking the opportunities it lines up for itself.)

The origin story of Makee is that she was a child labourer on a waste disposal planet, where she was beaten and tased by guards, and her boyfriend killed, for slacking off. Just in time, though, she’s rescued by Covenant Sangheili warriors, and we meet her as an adult who has seemingly been passing the time working on her Danaerys-from-Game-of-Thrones cosplay unbothered by the Covenant’s religious leaders. Why, you might ask, was Makee not massacred along with every other human on the trash planet? Because Makee, as it turns out, is a “Blessed One.”

I think this is the lossiest and most puzzling translation of ideas that HALO makes from the source material onto screen. For this, I need to explain some backstory—sorry, this is going to be an info dump, so I’ve hidden it behind a disclosure triangle.

TL;DR: In the HALO games, humans (through a genetically engineered racial memory or taboo) are capable of operating Forerunner equipment thus acting as a ‘Reclaimer.’ Spartans have an atavistic advantage, but the title of ‘Reclaimer’ is by no means restricted to them.

The titular HALO of the games, along with many other superstructures and artefacts (including the Keystones in the show) was created by an ancient species called the Forerunners, who largely disappeared around 100,000 years ago. As you might guess from their name, the Forerunners viewed their existence as fleeting, and considered it their philosophical imperative to hand over their stewardship of the galaxy to another society (‘Reclaimers’ of the Mantle of Responsibility.)

After various wars between the Forerunners and humanity (who, by the way, are an ancient spacefaring race who then regressed to a new Stone Age), the Forerunners designated humanity as their successors. In order to prepare us to assume the Mantle of Responsibility, the Forerunners planted a kind of racial memory (called a geas or genesong in Greg Bear’s lavish yet ponderous trilogy of HALO novels, THE FORERUNNER SAGA.) These provide a latent affinity for interacting with Forerunner technologies, such as a sense of déjà vu on stepping onto one of their installations or an instinctive understanding of how to use a console. The geas is stronger in some than in others, and as it so happens, it lines up with the genetic markers that were used to select the children for Project SPARTAN—because that was something that was also primed by the Forerunners, a society that made heavy use of genetic engineering to modify adolescents into caste-like social strata to which they were assigned for life.

Generally speaking, all of this is justification for the Master Chief getting to save humanity again, and again, and again. True, HALO is a game ostensibly for adults with a Mature rating, but underneath it’s a relatively facile hero’s quest story.

Technically speaking, the Master Chief is a chosen one in the most literal sense—he, as with the rest of the Spartans, is selected from humanity’s gene pool by Dr Halsey to become a protector of the peace (or a boot of the state, depending on your politics.) And yeah, it’s flimsy. It carries deeply uncomfortable eugenicist and master-race connotations by suggesting the Spartans are genetically superior. And if the Master Chief were a woman, she’d have been branded a Mary Sue non-stop for the past 2 decades. But at the same time, his genetic heritage is also the least important thing about the Master Chief. It’s only really ‘important’ in a brief scene in HALO 4 where mention is made of him having a genesong placed within him that contains genetic gifts—but it’s not clear if this applies to just the Chief, or the entirety of humanity. HALO doesn’t dwell on it too much, nor does it really care.

One would think that HALO The Series would, in an effort to produce something more palatable as a serious drama for adults, tone back these more fantastical aspects of the story in favour of a grounded approach that centres the Master Chief’s development as a character.

It does not do this.

In HALO The Series, the Master Chief, and to begin with, only the Master Chief, can activate the Keystone. The other Spartans try it, and it does absolutely nothing. It refuses to respond to anyone but John, for whom it does all manner of things. It can trigger a heart arrhythmia, show him suppressed memories of his childhood (with his two parents and his dog), release his shuttle from remote control, and cause a power cut to the UNSC headquarters in Reach City. Forget Clarke’s Third Law: in this case, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from a convenient device to move the plot along.

The explanation for this comes from Reth, an escaped Covenant captive who was driven to insanity by the experience and now lives in a cage(!) on The Rubble. He, in a Gollum-like hysteria, identifies the Master Chief as a “Blessed One”, i.e. someone who can use Forerunner technology, leading the Chief to go full Christian Bale Batman and bellow into Reth's face, demanding to know 'what' he is. John is the Special One, even amongst the Spartans, and so when Makee enters the equation, she is considered 'like him' (we're getting onto that.)

Why, you might ask, has the Master Chief been “blessed” but almost no-one else has? Because the Keystone has a twin which it must be plugged into to reveal a map to Halo. This Keystone is on Eridanus II, the Master Chief’s home planet.

This is an irredeemably stupid plot point. In the whole wide universe, the Forerunner artefact just happened to be buried on the planet on which the Master Chief was born? And John, the child of the colony’s leaders, just happened to stumble across it aged 5? And the young John’s drawings of the Keystone and the Halo were buried in a crate in the middle of a forest? What on earth was going through the producers’ heads when they came up with these details, which ultimately ties the Master Chief's fate even more closely to fate and destiny than the games?

Like the other changes made to HALO’s inner workings in the show, all of it is in service of what was presumably intended as a landmark plot beat. This time it’s a bizarre sequence in the Master Chief’s abandoned childhood home, where he puts on the Mjolnir helmet and enters a Second Life-style simulation of his childhood projected by Cortana (you can tell it's the future because they have the technology to render legs.) We cut away to a reverent ultra close-up on Pablo Schreiber’s face, as his lips twitch upwards in something approaching a smile. On paper, it should tug on our heartstrings, gladdening us and enraging us and stirring a pang of empathic regret. In practice, he looks like Monty Don on Gardeners’ World talking about how the smell of tobacco plants reminds him of his childhood.

Allusions to the Master Chief’s childhood have been done before (see David Fincher’s HALO 4 trailer Scanned, from 2012, with John as a child, on a beach, with his mother calling to him.) But these are all vague and nonspecific. You’re left to fill in the gaps yourself. His birth surname. Whether his parents were around much. What they did. There remains a sense of mystery to the Master Chief, because he can be whoever you want him to be.

What makes the Master Chief exceptional isn’t really his genetics, nor his upbringing in relation to the other Spartans. What matters is that he’s generally lucky, very brave, and stubborn to a fault. He’s less Anakin Skywalker or Harry Potter, more Frodo Baggins—simply the right guy, in the right place, at the right time, to save the world. Cortana chooses him as a battlefield partner in the games because he’s lucky, and because she recognises that they’d make a good team.

HALO The Series disregards all of this, deciding once again to fill in these gaps with crayon and turn them into more cheap objectives the Master Chief must complete to advance the plot. It was unnecessary to begin with. But in the choices made, the show pulls back the curtain of the Master Chief’s anonymity to reveal something utterly dull and uninspiring. Wow, you may think, if only I’d had parents who were high-achieving pioneers in an imperial system of expansionism, maybe I could save the world like the Master Chief.

And for all the show wants to be taken seriously by sophisticated TV-viewing adults, these choices mark a naïveté when it comes to the world that would’ve created Project SPARTAN. If John and Makee are both “Blessed Ones”/Reclaimers, they would share the genetic selectors for Project SPARTAN. Universal genetic screening was how they found John in the first place, and one assumes that at scale they would just screen everyone, including child labourers on garbage planets. If Makee’s Reclaimer/Blessed One genes are so strong, why was she not kidnapped and inducted into Project SPARTAN (if not the same cohort as the Master Chief)?

Or, to put it another way: if you’re an evil covert ops group who wants to kidnap "genetically superior" (yuck) children to experiment on and fashion into soldiers, and you have a limited budget, are you kidnapping the child of pioneering botanists who are leaders of their own colony world, or are you going to kidnap the presumably orphaned girl who no-one will miss from the garbage planet?

HALO The Series stubbornly refuses to engage with this, and there is absolutely zero excuse for it not to. Karen Traviss is an author whose political views I find detestable in every sense, and yet she, of all people, was acknowledging the class aspect as far back as 2014. In her KILO-FIVE TRILOGY of spin-off novels, we meet Spartan washout Serin Osman, and in its conclusion, MORTAL DICTATA, we learn Serin’s mother was a sex worker with a drug habit, and that UNSC operatives lured her away with food and didn’t bother to replace her with a clone. The apparatus of the state undertaking this kind of callous economising is not an especially sophisticated class analysis, but it is incisive, because it’s plausible.

It is also the kind of thing that’s absent from HALO The Series, which shies away from the genuine human interest aspect in favour of a story about a nobleman in all but name. Instead of being a story about being the last of your kind facing down an existential threat, the series casts HALO as the tale of a chosen prince who must save the world and get the girl.

…oh yes. Getting the girl. We should address that.

Deep breaths.

PART IV. I guess we need to talk about how they f*cked

The Master Chief had sex and it wasn’t even him and the Arbiter lovingly blowing each other's backs out before the final level of Halo 3

(Yes, really.)

On 10th May 2022, a day that will forever be seared into my memory, I got a text from an old friend who I met on a HALO fan site's IRC channels in the late 2000s. I reproduce this conversation in its entirety below.

Reader, I regret to inform you that I was correct. Because in HALO episode 8, the Master Chief has sex with Makee.

Here’s how we get to this point:

- Makee, posing as an escaped Covenant captive, hijacks a UNSC ship and kills everyone onboard with Hunter worms.

- Since the ‘pretend to be an escapee’ act worked first time, the Covenant tries again, this time leaving Makee behind on Eridanus II after a battle, where she’s found by the Master Chief.

- Makee is brought to Reach by the UNSC, who don’t entirely trust her, but find that, like John, she can activate the Keystone.

- The Keystone causes Makee and the Master Chief to share a vision of a Halo ring.

- They go for a walk in a park with some nice trees in blossom.

- The Master Chief gets her a book.

- They have sex(!)

- Makee betrays the Master Chief, steals the Keystone, and escapes Reach.

- The Master Chief goes after Makee to recover the Keystone.

- Makee is killed in the encounter, which makes the Master Chief sad.

All of this happens over the course of three episodes towards the back of the series. For five episodes, the Master Chief and Makee never so much as interact. Just over an hour of screen time after their first encounter, Admiral Parangosky is watching surveillance footage in horror as the Chief and Makee go for a walk in a park.

And then, they have sex. They do not bang or fuck or screw, nor do they get it on with each other or make love or even WooHoo like this is the Sims. They take each other’s clothes off and trace each other’s scars, silently share chaste-looking kisses, and sleep in the same bed. They don’t even spoon.

Is it a problem if a sex scene is gratuitous? Of course not! Sex is part of the human experience for many of us. The problem is not that there is a sex scene. The problem is that it’s bad. Despite Schreiber and Murphy’s valiant efforts, the Master Chief and Makee have all the chemistry of dental putty.

Watching it, I was reminded of RS Benedict’s article for Blood Knife, Everyone Is Beautiful and No-one Is Horny: there’s gentle half-lighting, there’s tender cello music, there’s Charlie Murphy’s sparkling eyes and Pablo Schreiber’s pumped deltoids… and despite all that, they look like dermatologists examining each other’s scar tissue for necrosis. Considering neither of the characters would ever have had sex with another human before, there’s no awkwardness, there’s no fumbling, there’s no messy laughter as they fuck up and try again. It’s boring and pedestrian and safe and I cannot believe for one second that these two people actually want each other. Ari Notis for Kotaku writes that the encounter is “about as steamy as the iconic Cold Storage multiplayer map.” The sexiest aspect is the cut-away shots where we see Cortana, as noted in Jessie Earl's review, learn in real-time that she likes to watch.

In the games, the Master Chief doesn’t express carnal interest in anyone. It’s implied that he might be what we would call ‘asexual’ based on side-effects of Spartan augmentations altering hormone levels, and his general psychological conditioning to be an instrument of war above all else—or that may just be the way he is. But he does share a deep bond with some people, such as the other Spartans, and particularly with Cortana, where their connection ranges from snarky remarks of the kind you’d expect from a comfortably married couple or a decade-long buddy-cop partnership, to the devastating goodbyes at the end of HALO 4 and HALO INFINITE. Steve Downes and Jen Taylor’s natural rapport produces some truly affecting dénouements that are surprisingly tender for a sci-fi shooter game.

The HALO universe declines to detail the Master Chief’s sexuality, leaving this side of him stubbornly unexplored. If you think the Master Chief is asexual and gets his kicks from war—well, he is and he does. If you choose to believe he and Cortana have some kind of in-brain cyber-sex—they could, and they might. If your headcanon pairs him off with one of the other Spartans, or with Miranda or Johnson or Parisa from that spinoff story or Palmer or the Pilot, or that him and the Arbiter are in a star-crossed inter-species tryst, that works too.

Is this impossible in a TV series where we’re committed to exploring the Master Chief as a character with wants and needs rather than an exposition delivery system? Meh. I’m probably bitter about the show ignoring my own headcanon, i.e. the Chief being asexual, or not caring to explore his sexuality. I don't believe there was any conscious effort to make the original game-verse Master Chief asexual or 'not straight'—it would definitely be a reach to call him an asexual or queer icon.

But I also think we should ask a different question: even disregarding this, would the Master Chief have sex with Makee?

No, because (a) she’s obviously a spy, and (b) it’s a fucking war crime.

Chief’s (lack of) sexuality is not sacrosanct to the character. But him being a professional soldier who's spent almost his entire life in the military is. To all intents and purposes, despite her cell looking like a Scandi-inspired sitcom set, Makee is a prisoner of war. The Master Chief is amongst her captors. She cannot legally consent to sex with someone who is holding her prisoner and interrogating her. Despite their sexual encounter apparently being consensual in the moment, even the UNSC must have rules on the book that dictate how extremely inappropriate any kind of fraternisation would be. Is Admiral Parangosky tolerating it in the hope the Chief could feed them intelligence having seduced Makee? Grossly immoral, yes, and also something that happens in the real world—this is not something I’d put past Parangosky, and definitely not Halsey.

I stress that my problem with this storyline is not that "a character did a problematic thing in a TV show," nor even that "the Master Chief did a problematic thing." 'Problematic' behaviour by fictional characters is typically the source of conflict, and the foundation stone of great drama. The problem is that HALO does not even appear to realise that it is problematic. It is disinterested in the moral acceptability or otherwise of the Master Chief and Makee being in a relationship, or of the state using a sexual relationship as a form of subterfuge to obtain intelligence. When there are consequences, the show's main takeaway as expressed by Parangosky is "the Master Chief should not be emotional on the battlefield" rather than "captors having sex with prisoners is bad and inappropriate."

It brings up echoes of how the show handles Adun's casual sexual assault of the about-to-be-eye-poked Halsey clone in episode 3—or rather, how it doesn't handle it, with no consequences or repercussions. Similarly, in the Makee case, the show carries on as if this is normal and nothing untoward has happened. We are supposed to accept at face value that the Master Chief was instantly attracted to a woman he’d never met before, had sex with her despite the obvious ethical complications of them doing so, and the entire weight of the UNSC bureaucracy’s response to it is ‘congratulations on the sex.’

Add to this that Makee, from the moment she is left on Eridanus II, might as well be walking around with a neon sign above her head saying “I AM A SPY.” You could argue that it’s a casual encounter that doesn’t mean anything and just happened (which might be more believable if they had a shred of chemistry.) But the show’s desperate to have us believe that Chief and Makee are in love now. Is it trying to show us how lust or emotions can make us ignorant of an obvious threat? And is this kind of glamour also supposed to apply to the entire military apparatus that facilitates Makee’s debriefing and continued detention, or just to the Master Chief?

Exploring the Master Chief’s sexuality was always going to be controversial. For what it’s worth, I’m all for it (if done properly.) But as with so many things in HALO The Series, the furore over surface elements obscures the deeper structural problems with characterisation and texture. The romance is unexciting and unearned, and right at the end, HALO discards Makee even more decisively than it discarded Kwan Ha, killing her off so that the Master Chief can get sad and do the big pivotal thing at the end.

This could all have been avoided in the planning stage if someone had sat down and asked: would the Master Chief, Spartan-117, flout every regulation on the book and have sex with someone who is clearly a mole? Is the TV Chief a more interesting character than the game Chief for him having done so? Is he more relatable? Is he more believable? Is he more likeable?

Maybe he would be… if only they’d convinced me that these two people even so much as liked each other.

PART V. Missing the point of the Master Chief and Cortana

"The pressure to be an Iron Man for grown ups is holding Schreiber’s performance back"

In HALO The Series, the Master Chief is very rarely allowed to be the Master Chief. Aside from the sex thing (which is bad) there is something generally off about his behaviour, and it makes it hard to recognise and root for this character in the same way we root for the Master Chief in the games. True, this Master Chief is earlier along in his career than the Chief we meet in the games—the first game’s prequel, THE FALL OF REACH, ends, unsurprisingly, with the Covenant finding and sacking Reach, a cataclysmic turning point in the Chief’s character arc which has not happened in the show yet. But still, there’s something off. Pablo Schreiber’s John, while occasionally showing hints of being the taciturn and statuesque figure with a touch of cordiality we would recognise as the Master Chief, seems to mainly be set in the cast of a different kind of action hero.

As our protagonist, he was always going to have to talk more than he was in the games. It was also a given we were going to see his face at some point. But none of these, in themselves, are problems.

And it’s not like the Master Chief is now some garrulous over-talker, or has started giving stirring, inspiring speeches. Just now and again, there’ll be a well-placed silence or pause that ‘seems’ very Master Chief-like. But what does feel odd is an uptick in wisecracks and witty remarks delivered at inopportune times. In one of the action set pieces, Chief asks “mind if I drive?” as he hijacks a Warthog—but he’s practically gasping for breath because he's been giving chase. As Silver Team drops onto a Covenant planet amongst a horde of Grunt patrolmen, he growls “afternoon” as one of them gets squashed. The game Master Chief does have a snarky sense of humour, yes (there’s that bit in HALO 2 where he surprises a Grunt and says “boo”) but that’s not his whole personality, and I don’t think the Master Chief would jeopardise an active combat situation by wasting his breath and polluting his communication lines with unnecessary noise.

Here’s my theory: there was a tone meeting at some point during production and one of the notes—probably from someone unfamiliar with the source material—was “make the Master Chief more like Iron Man.” And make him more like Iron Man they did. Snark and backchat added to battle scenes in ADR. Reverse shots from a virtual camera inside the Master Chief’s helmet, like all those ultra close-ups from inside Iron Man’s helmet of Robert Downey Jr’s face plastered in make-up as he banters with J.A.R.V.I.S.

But the Master Chief is emphatically not Iron Man, so it doesn’t really work. The aspect of HALO that requires Master Chief to be an aloof, emotionally-damaged loner is at war with the desire for a more conventional ‘action hero’ Master Chief reminiscent of Harvey Keitel, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and The Rock. The result leaves no room for texture or subtlety, something the show should have in spades—by means of giving the Master Chief an actual human countenance—but cannot, because as much as HALO The Series is only interested in the Master Chief, it also needs him to move the plot along, meaning that a lot of his dialogue feels like connective tissue.

By contast, Steve Downes’s Master Chief from the games arose from a minimal character sketch suggesting a Clint Eastwood-style character of few words. This established a baseline so that when the Master Chief did choose to be more talkative (giving the Covenant back their bomb in HALO 2, promising to help a dying Cortana in HALO 4, a heart-to-heart with the hysterical Pilot in HALO INFINITE) it carried more weight and intention. This was supplemented with body language in a way HALO The Series seems unable to manage. Sure, the animation looks dorky in HALO: COMBAT EVOLVED when Chief puts his hand on the shoulder of a terrified Marine in a lifeboat, but it tells you more about who this person is and what he means to these people than any number of pithy one-liners could manage.

There’s something a bit odd about his connection with Cortana, too. There’s a delightful slapstick moment in HALO: COMBAT EVOLVED where Cortana accidentally teleports the Chief upside down, and he whacks the side of his helmet on standing up. Shortly after, he gets his own back by crashing a vehicle and jumping from it at the last minute. “You did that on purpose,” Cortana says, and you can sense that if she still had a face, she’d be smirking. The synergy between them is electric. The Master Chief and Cortana are, in Cortana’s own words at the end of HALO INFINITE, “a team. Perfectly suited. Perfectly matched. Perfectly... perfect.”

HALO The Series changes this dynamic significantly by introducing Cortana as a babysitter for the Chief after he refuses to murder Kwan Ha and goes AWOL. More than that, there’s a new element in play. The series has Halsey’s ultimate plan to be for Cortana to “overwrite Spartan consciousness”—i.e. take control of John’s entire body, wipe everything from his brain and effectively turn him into an automaton. The Chief’s misbehaviour is used as leverage by Halsey to get the go-ahead to pilot the “Cortana system”—as if every Spartan is eventually going to have their consciousness terminated and replaced by an artificial intelligence spawned from a Halsey clone’s brain with that awful eye-poke machine.

Cortana has always lived somewhere between the data chip that plugs into the Master Chief’s suit and in the actual synapses of his brain—to some degree, they share headspace—but what the TV show proposes is something entirely different.

I’m going to stick my neck out and say this could’ve worked. HALO’s spiritual predecessor, Marathon, has a surreal sequence in its final game where the player character (Mjolnir Recon cyborg number 54—sound familiar?) uploads the series’ main AI character, Durandal, into his own brain. Maybe this is where the inspiration came from. And as with the ‘emotion chip’ thing it’s feasible that some clueless stakeholder might ask, “why can’t you just replace their brains?”

But as with every trickshot that HALO attempts to pull with changes for the TV show, it is done with a lack of finesse and vision and leads to this storyline falling flat on its face. The rationale for it is desperately unclear. If Doctor Halsey wanted her own brain and only her own brain in a super-soldier’s body, why would she not have used flash clones? Why not simply build the Mjolnir armour as a humanoid drone rather than a suit with an actual fleshy human inside it?

If we give the questionable sci-fi logic the benefit of the doubt, in the circumstances HALO The Series presents, it’s understandable that the Chief’s working relationship with Cortana would get off to a rocky start. Even so, his behaviour is waspish and unusually dismissive. Trying to turn her off in front of other members of his fire team. Threatening to cut her out of his neck. Telling her to ‘stop talking because he can’t hear himself think.’ The Chief comes out of it looking like an arsehole who’s needlessly unpleasant to Cortana.

For all her supposed tactical genius, Cortana doesn’t really get much to do in this show either. She helps the Master Chief cut the emotion chip out of his lumbar region by telling him where to put the knife, she helps him filter a spreadsheet of planets, she helps him explore the weird virtual-reality replica of his childhood home. When she finally gets to the battlefield, the Chief all but tells her to ‘shut up’ because he finds her suggestions about when to switch weapons overbearing. When she proposes a dangerous space mission in the final episode, she inexplicably withholds a crucial piece of information until the last moment, thereby putting everyone in danger.

This contrasts poorly to the games, where Cortana is Virgil to the Master Chief's Dante, the one doing all the talking, exploring the world with you and driving the plot forward. She is there to understand things when you (as the player, or the Master Chief) don’t. She calls in airlifts, suggests battle tactics, disarms bombs, and breaks into alien computers. The Marines and officers call her “ma’am” and follow her orders. Cortana’s competence and value are never called into question; when someone does choose to ignore her in HALO 4, it’s the basis for a mutiny. Cortana is more critical to the happenings of HALO than Spartan-117 himself. They are, indeed, a team, perfectly matched, perfectly perfect.

The Cortana that HALO The Series gives us initially behaves more like the Master Chief’s secretary (and a spy for Halsey.) Forget an ultra-powerful superintelligence with access to the sum total of human knowledge—this Cortana feels like the thing that lives in your Windows taskbar to tell you about your next appointments and appears in cringey TV adverts with Clean Bandit (all the while reporting your searches to advertisers.) She is a sideshow because HALO, despite its ensemble cast, is interested in the Master Chief, and the Master Chief only.

So the only tension in Cortana’s character arc is ‘will she get to replace the Master Chief?’ This is set up in episodes 2 and 3, and then almost irrelevant until the season finale. When it finally happens, the Master Chief is at death’s door, his ‘girlfriend’ (who he’s in love with, remember?) has just been killed by Kai to knock him out of a Keystone-induced trance, he has been mortally wounded, and in extremis, he consents to Cortana taking full control of his body.

We are expected to treat this as a big emotional moment and payoff and not ask questions, despite the fact that the Master Chief only really acknowledged Cortana as an ally or accomplice at the start of the same episode, and we’ve likely already forgotten the setup in episodes 2 and 3. Much like the romance with Makee that came out of nowhere and was cut short before it could be anything good, HALO focuses excessively on the bookends of its story arcs but abbreviates everything within.

It’s especially puzzling because we already saw Cortana take control of the Master Chief’s body, several times. It’s established early on that she can put him in ‘stasis mode,’ causing his eyes to white out like he’s been possessed by the Devil—but the Keystone will only react to him ‘as John,’ so she’s forced to relinquish control.

It’s unclear what exactly is different between the ‘stasis mode’ and what happens at the end of HALO episode 9. Has Cortana overwritten the Master Chief’s consciousness? Has she merged herself into him? Did she simply take control of the Mjolnir suit, moving the Chief’s carcass within around like a macabre Thunderbirds puppet? Is this the permanent state of affairs now?

This ambiguity sets up the final ‘moment’ of HALO season 1, where, much like at the front of the series, it almost does something profound. Kai sits next to this terrifying new figure in the pilot’s seat of the Pelican, and asks, “John? Is that you?” This question is left unresolved as we zoom ultra close on Chief’s visor.

This appears to borrow from the very final scene of Years and Years, a 2019 drama written by Russell T Davies which is one of the finest pieces of television this century. It is political, it is radical, it is imbued with warmth and humour and biting satire. Its ending is the jewel in the crown, a distillation of its core theme into five exquisitely-written, acted, and directed minutes. Years and Years is a long-standing labour of love for Davies, who dedicated the show to the memory of his husband who died of cancer during production.

I don’t think the similar-feeling final scene of HALO is bad in itself, per se. It’s just that it came out of nowhere. The idea of the Master Chief merging with Cortana isn’t something that’s even broached in the games. It’s a Chekhov’s gun the show has given itself to set up, but without enough work having gone in to explain the stakes and raise tension towards the final pivotal event. For this reason, it is almost the opposite of the Years and Years ending it pays hômage to—because we have not grown to care about these characters or this particular topic, it feels like something tacked on at the end to say something ‘deep.’ It’s another instance where HALO The Series forgets that storytelling is mostly about the journey, not the destination, and in doing so commits the cardinal sin for any HALO franchise media by being generic and dull.

And in all this, we still feel like we have barely met this show’s version of its main characters, the Master Chief and Cortana, at least not to the stage where they are recognisable as such. Pablo Schreiber’s Chief is grumpy and distant, and one struggles to think he would have comforted that terrified marine on the lifeboat we see him do in the first 20 minutes of HALO: COMBAT EVOLVED. Cortana never really gets to be the battlefield commander and tactical genius we see in the games—not until the very end.

It’s a shame because show is capable of telling a compelling story in the rat’s nest of contradictions it’s built itself. For a taste of how it could’ve been, look at Kai-125 (played by Kate Kennedy), who appears to be a renamed version of the Master Chief’s squadmate, Kelly-087, from the original HALO books and games.

Kai has a stronger reaction to cutting out her emotional regulator than the Master Chief, dying her hair with gun grease, showboating her augmented strength on the base by lifting a Warthog, and striking up a sororal bond with Miranda Keyes. She also begins asking questions about morality and about Dr Halsey, which builds to a top-tier climax with an action set piece in episode 9: Kai leaps aboard Halsey’s getaway ship during take-off, demands to know her real name, and kills the creepy Adun when he attacks her. Shortly afterwards, she climbs out of the wreckage of the crashed ship and looks like a badass doing so. While Kai is recognisably a Spartan, Kate Kennedy strikes a nice balance between an efficient and professional soldier and a compassionate hero.

Critically, unlike the Master Chief in this show, Kai is actually a likeable character. Kennedy’s natural warmth as an actor shines through, and the script offers her a level of progression that gives us someone to empathise with and root for, allowing her to contain multitudes rather than being a one-note plot vehicle. Her interactions open a window for Olive Gray’s Miranda to shine. In the triangle of ‘affable,’ ‘gauche,’ and ‘professional killer,’ Kai sits dead-centre, almost perfectly in the Master Chief Zone—more so than the show’s interpretation of the Master Chief himself.

Would the show have been better if they’d consolidated the two plot lines and had HALO The Series starring Kate Kennedy as Master Chief Jane-117? Maybe. It does feel like the showrunners focused excessively on making the Master Chief match the physical description in the books (tall, white, brown hair, blue eyes) without stopping to think what gave him such a universal appeal as a character. Maybe casting a Master Chief who looked radically different would’ve helped focus minds on making the dialogue and interactions of the character feel true to the game incarnation. (I would’ve suggested names like Samuel Anderson, Gwendoline Christie, or Brian J. Smith—to my mind the Master Chief should look and move like an old tree with a thousand yard stare.)

But Pablo Schreiber was the Master Chief we got. And while we get flashes of brilliance from him with the odd line of dialogue or silent stare that ‘feels’ true to the Steve Downes Master Chief, Schreiber is expected to be too much of a wise-cracking, gun-toting, testosterone-fuelled action figure for the less conventional aspects of his character to shine through. The pressure to be an Iron Man for grown ups is holding Schreiber’s performance back. And with the sheer amount of screen time HALO insists on devoting to this version of the Chief, that’s a problem.

PART VI. A cursed production?

"This show has Microsoft's fingerprints all over it"

It is no secret that the production of HALO has been a drawn-out mess, and as with any project that’s been in development hell, it really needed just that little bit longer. The first series of anything is always going to feel like a disaster from the inside. But it certainly feels like this show has been uniquely troubled in the challenges it had to work around. Keep in mind a good amount of this is educated speculation.

Generally speaking, the visual effects in the show are fine, framerate issues aside. One of the VFX houses, Pixmodo, who were responsible for some of the environments and for Cortana, have proudly trumpeted their VFX reel for HALO, which looks great. But they are but one of no less than nine VFX houses credited on the finale. This is not unusual for TV shows these days—there is a disturbing trend for studios to exploit visual effects artists, and to simply hire more houses (at rock-bottom rates, leading to crunch, bankruptcies, and redundancies) to turn shots around faster and rush the show/movie out of the door.

I can't speak to whether this happened on the show or not (I'd be interested to hear from VFX artists who worked on it) but despite an enforced hiatus during COVID that should have allowed for some slack with material that was already in the can, HALO is riddled with visual or continuity errors that could’ve been fixed given a little more time. Clearly unfinished visual effects shots (like one of an assault rifle falling to the ground in episode 1 with broken textures.) A nude scene where an actor’s modesty sock is clearly visible in a wide shot. Close-ups on the face of Makee, who has supposedly been living with the Covenant for over a decade, where you can see the grain of her make-up. Cortana shots where her motion performance slips into the uncanny valley. It certainly feels like the production staff and artists had to cut corners to make a release date, rather than the network waiting until the show could be finished before airing it.

There also appears to have been a fair bit of churn amongst the show’s personnel, which is well-documented in an article in Variety. The original director, Rupert Wyatt of Dawn of the Planet of the Apes fame, pulled out due to production delays, which ultimately led to one episode being shaved off Showtime’s original order of ten for the first season. Steven Kane, one of the showrunners, claims to have gone through 265 drafts of the script (which, assuming that’s accurate, would outnumber even the 191 drafts that Michaela Coel wrote for I May Destroy You.) The majority of the production took place in Budapest (maybe to take advantage of the Hungarian government's generous tax rebates) and that led to the other showrunner, Kyle Killen, dropping out due to family commitments.

And even so, after hundreds of drafts, something seemed uncomfortably familiar when watching the show. I'm a fan of the HALO franchise, and also a lifelong (reluctant) user of Microsoft software. I know how executive indecision and overcorrecting for fan feedback has led to plot threads being abandoned and character development being reversed. I know how wildly quality can vaccilate even in the same game. I know how the books following the Master Chief tend to be more risk-averse than the other spin-offs featuring different characters. And I know how executives clashing horns within the company results in baffling, customer-hostile product choices. When I watched HALO The Series, I thought to myself: "this show has Microsoft's fingerprints all over it."

To understand the level to which Microsoft's internal politics and executive suite ego has affected the development of the HALO franchise, it's worth looking into a tale from the mid-2000s, recounted in Jamie Russell’s book Generation Xbox: How Videogames Invaded Hollywood: the infamous story of "Master Chief Monday." A section of that Variety article above recounts that, in an incredible display of corporate hubris, Microsoft sent actors in Master Chief cosplay to the offices of Hollywood studios, armed with Alex Garland’s screenplay and an enormous rider that demanded vetos on directors and casting, scrutiny of every cut during post-production, and 60 first-class airfares to the premiere for Microsoft’s own executive suite.

Hollywood, Microsoft, and the landscape of TV and film may have changed in the last 17 years, but I am absolutely willing to believe both that (a) Microsoft retains an iron grip over the franchise, (b) their corporate culture means they doesn't have a clue what to actually do with it, leading to careerist meddling, jostling, and interference to the detriment of the final product.

What we do know about the production is that it moved to Toronto (likely for re-shoots) in late 2020, and would not return to Budapest until the following year, when US cast and crew were exempted from the EU's COVID entry ban. What we also know is that late 2020 was around the time it emerged that Natasha McElhone, who had been announced as both Halsey and Cortana (roles which are traditionally dualled) would now only be playing Halsey, again due to some kind of scheduling issues. Jen Taylor, who played both characters in the games, would be stepping in as Cortana.